|

THE 'COMMON' GOLDFISH

LES PEARCE |

Even its familiar name, the 'Common' Goldfish, serves to belittle its stature among those who, for one reason or another, do not wish to understand this species further.

For years, probably centuries, seeing small Goldfish strung up in little jars and latterly, in plastic bags, was commonplace at fairgrounds. “Throw three darts at a board,” or “Throw a hoop over a jar to win a Goldfish,” the stall-holders would cry. How degrading! How many other animal species has this commonly happened to?

I wonder how many Goldfish lost their lives in those tiny jars and plastic bags.

Indeed, how many more suffered the same fate at the hands of their new owners who, totally ignorant of their prizes' needs, promptly tipped them into a little bowl or jar and either 'fed them to death' or starved them to death.

Thankfully, in recent years such practises have become less commonplace and are viewed with greater importance. However, the inferior image and the stigma attached to the Goldfish remain. Today the Goldfish is considered by some to be a beginner's fish, a fish to make all your mistakes on before progressing to 'proper' fish. The reasons for this are manifest.

The Common Goldfish is easily obtained, plentiful and colourful; it does not require artificially high water temperatures when kept in temperate climates and will suffer and survive poor water conditions with greater resilience than most of its more illustrious cousins. It is, therefore, not only very cheap to purchase but, to the unenlightened, would seem to be very cheap to accommodate.

The life of the Goldfish at the hands of the novice is, to say the least, something of a lottery. It is true to say that some beginners in our hobby try to do things the 'right way'. They read books on the subject, ask questions and generally try to educate themselves in the requirements of their new pet. While they will undoubtedly make mistakes as they learn, they are at least trying to meet the fish's most basic needs. A fish in the care of such a person stands a more than average chance, not only of a long life, but also a comfortable one.

Not all Goldfish are so lucky. Some find themselves sentenced to life in a tiny, unfiltered bowl, 100 percent water changes every few days with little or no regard to the quality of the new water or as to whether it contains harmful chlorine. Or, perhaps, to the other extreme, no water changes at all. It is a miracle that any such unfortunates manage to survive this but, somehow, many seem to do so.

Opinion remains divided regarding the origin of the Goldfish. There can be little doubt that it is very closely related to the Crucian Carp, Carassius carassius, but the question remains whether it is actually a direct descendant or just a close relative.

It is certainly true that if allowed to reproduce in the wild, without the intervention of man, the Goldfish will, over a few generations, revert to something very closely resembling the Crucian Carp.

It is certainly true that if allowed to reproduce in the wild, without the intervention of man, the Goldfish will, over a few generations, revert to something very closely resembling the Crucian Carp.

The question is, is the resulting fish the wild form of C. auratus or is it a reversion to C. carassius? According to the FBAS fish guide, Booklet No 3, Dr Yoshiichi Matsui, aquatic author and Professor of Fish Culture at Kinki University in Japan, believes that the former is true and that the Crucian Carp is the ancestor of the Goldfish. This publication also quotes Dr Otto Schindler's opinion that while the two species are closely related, there is a dark blotch present on the caudal peduncle of the Crucian Carp that does not appear on the reverted form of the Goldfish.

Other differences exist between the two species. The dorsal spine in the Goldfish is coarsely serrated but not so in the Crucian Carp; the edge of the dorsal fin of the Common Goldfish is concave whereas that of the Crucian Carp is convex; the body of the Common Goldfish is thought by some to be more elongate than that of the Crucian Carp and the scale count along the lateral line is reported to be 25 to 30 in the Common Goldfish but 28 to 35 in the Crucian Carp, indicating a larger scale size in the Common Goldfish.

The early history of the cultivation of Goldfish is equally unclear but it is generally accepted that by the time of the Sung Dynasty, around 1000 AD, Goldfish were being captive bred in China. It was not, however, until around 1500 AD that Goldfish first appeared in Japan and they did not find their way into Europe until the 17th century. The Goldfish was first zoologically classified as Cyprinus auratus in 1758 in a book by Von Linné entitled Systema Naturae.

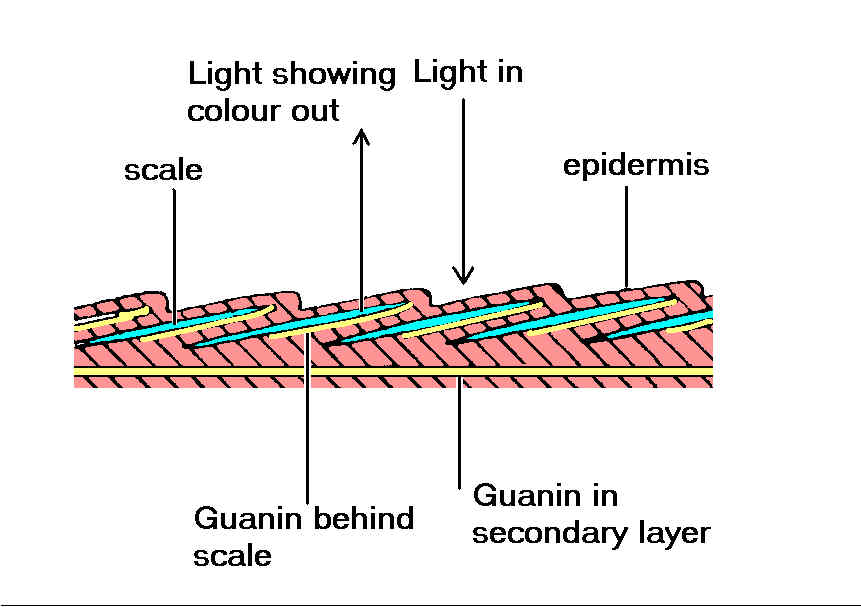

The Goldfish, like all other fish, is a complex living being. Contained within the dermis, or lower skin layer of the Goldfish, is a substance called guanine. This is a silvery-white colour and very reflective. It is this guanine which reflects light through the transparent scales of the fish to give it a shiny appearance. Generally, Goldfish are placed in three separate groups dependent on the amount of guanine present and how it is disbursed within the fish. We know these groups as Metallic, Nacreous and Matt.

In the metallic group the guanine is placed in the upper areas of the dermis, allowing good reflection of light through the scales and giving the fish the appearance of burnished metal.

Nacre means Mother-of-Pearl so, taking things literally, a nacreous fish has a Mother-of-Pearl sheen to it. This is caused by the almost complete absence of the upper layer of guanine allowing the layers situated deeper beneath the dermis to show through and giving the fish its silky lustre.

A matt fish has a complete lack of guanine and, as it has no reflective tissue, a totally matt appearance all over its head and body.

The colour pigments present in any Goldfish are a combination of yellow and red-orange, known as lipochromes, and black, known as melamines. In addition to these three colours there is the red colour in the blood (haemoglobin).

A metallic fish is usually a reddish orange or a deep chrome yellow. A lack of pigment will also cause some fish to be partially, or even completely silver. The olive-green colour found in reverted or 'uncoloured' Goldfish is created by a mixture of all three pigments at various depths in the dermis.

The term 'uncoloured' is usually applied to metallic Goldfish which do not develop the desired red-orange or yellow colouration, or even silver, but remain an olive-green colour for their entire lives. I feel this is something of a misnomer as, strictly speaking, the term 'uncoloured' implies a total lack of pigment and, as previously stated, a total lack of pigment leaves the white of the tissue and the reflective silver of the guanine.

The nacreous fishes are by far the most colourful of the three groups. The colour pigments mix and overlap at different depths to produce a stunning range of colours including pink, red, yellow, blue, grey, black, violet and brown. The best fish have an underlying base colour of a beautiful blue created by the presence of melamines, or black pigment, deep within the adipose tissue, beneath the dermis. Interspersed over this blue is a mixture of some or all of the previously listed colours creating, in good examples, a stunning array of colour to compete with almost any other species of fish.

Matt fish are usually pink and do not have any iris to the eye, the eye is completely black. This is sometimes known as button eye or shoe-button eye. The pink colouration is caused by the haemoglobin in the blood and is particularly evident in the gill areas where the blood flow is concentrated to absorb oxygen from the gills.

The nacreous and matt versions of the Common Goldfish are known as the London Shubunkin. The standard for the London Shubunkin is identical to that of the Common Goldfish in every other way.

The next time you see a humble Goldfish for sale at your local dealer's, don't think of it as a poor relation to your expensive tropicals at home. Consider instead the centuries of selective breeding and loving care that have gone into making it what it really is today ... an attractive and challenging branch of our hobby, a real alternative for anyone looking for 'something different' to further their interest.

You might even start to compare individual specimens to the standard books and then, before you even realise it, you have 'got the bug'. You may wish to try your hand at breeding Goldfish, selecting the offspring that best meet the standard you are aiming for, or you could try showing your newly acquired Goldfish. You will start to find out if your interpretation of the standards matches that of the judges and you will learn what to look for and what makes one Goldfish a more desirable specimen than the one next to it. The next thing you will want to do is to find out about more exotic varieties of Goldfish that are available, select your favourite varieties and maybe keep some of those ... but that is another subject.

© Copyright - Les Pearce 1998, revised 2001.

Bibliography and further reading:

FBAS Booklet no. 3 - Fish Guide

FBAS Booklet no. 4 - Goldfish Standards

Fancy Goldfish Culture - F.W. Orme - Spur Publications

Goldfish Guide (3rd Edition) - Dr Y. Matsui & Dr H.R. Axelrod - TFH Publications